Kevin Jared Hosein’s masterful Hungry Ghosts is set in 1940s rural Trinidad and tells of two households.

By Alice O’Keeffe

Kevin Jared Hosein’s masterful Hungry Ghosts is set in 1940s rural Trinidad and tells of two households. In the grand house of the estate farm, at the top of the hill overlooking the village, live the Changoors: Dalton, a man whose source of wealth is murky and unclear, and his much younger wife Marlee. At the bottom of the hill lies the barrack, a dilapidated building constructed of wood and tin with a leaking roof, divided into rooms that are occupied by whole families. Among them are the Saroops: Hansraj (Hans), his wife Shweta and their teenage son Krishna.

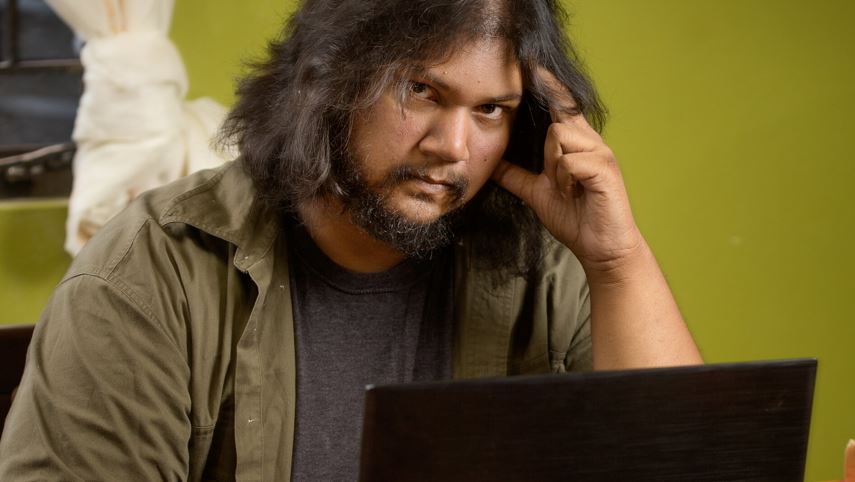

The novel opens in the immediate aftermath of Dalton Changoor’s sudden and mysterious disappearance. After a series of disturbing events—two guard dogs are found dead and a series of ransom letters arrive—Marlee begins to fear for her own safety. So she persuades Hans, who is one of three farmhands who work for her husband, to take on more work as a nightwatchman and guard the house, in case whoever came for Dalton comes back for her. And then? “Danger ensues. Not just physical danger, but a kind of emotional danger,” says Hosein, thoughtfully, in his melodic Trinidadian accent when we meet in central London.

So keen is Bloomsbury on this acquisition that it has flown Hosein from his home in Trinidad to London for a pre-publication visit, and I have just watched him hold a roomful of journalists rapt. He teaches biology at a secondary school, he says, when we sit down to talk afterwards, by way of explaining his ease at speaking in front of a crowd.

The novel has so far drawn praise from Bernardine Evaristo (“an astonishing novel—linguistically gorgeous, narratively propulsive and psychologically profound”) and the late Hilary Mantel (“deeply impressive… Energy and inventiveness distinguish every page”).

Darkness and mystery

The title Hungry Ghosts is an allusion to insatiable desires, Hosein says, “which a lot of these characters feel for things they cannot attain… yet they yearn for them.” The novel illuminates the grinding poverty of those living in the barrack, where “the corrugated iron would ding with each raindrop”, a shelter so basic it cannot keep the rain out, nor contain the ambitions of those who dwell within it. Shweta longs to buy a plot of land in the village and escape from the barrack. Hans, once he has had a taste of a different life up at the big house, wonders how he can bear to go back. And Marlee, who has reinvented herself to rise to the position of lady of the house, is now in desperate straits.

As the story unfolds in lush, rural central Trinidad and the mystery of Dalton’s disappearance deepens, the fates of the two families become dangerously intertwined as violence, religion and class come into play, motives are revealed, and the novel builds to a gripping climax.

Hungry Ghosts arose from a conversation Hosein had with his grandfather years ago. In 2016, Hosein was the Caribbean regional winner of the Commonwealth Short Story Prize (he was later named overall winner in 2018) and so was commissioned to write a non-fiction piece about any aspect of Trinidad. He chose to interview his grandfather about his life in the village as a young man in the 1940s. It was a dark time: the US military was stationed on the southern Caribbean island at the invitation of the British, who were concerned about German submarine attacks. But also, as Hosein puts it, the British were “loosening their grip on everything” and the end of colonialism was on the horizon. His grandfather’s memories were fascinating and Hosein found himself intrigued enough to want to fill in the gaps with research and conversations with a local historian. During lockdown he stayed up until 2 a.m. writing the novel, after lesson-planning and marking.

Trinidadian writer Harold Sonny Ladoo’s novel No Pain Like This Body (recently published for the first time in the UK by Vintage Classics) was also an inspiration. “That’s the book that [Hungry Ghosts] stands on, in a way. Although it’s set much earlier, in the 1900s, it has a similar setting based around children living in a barrack. So that formed what I would call the base, or the stock, for [my] book.” Cormac McCarthy was also an influence: “There’s a way in which he writes about darkness in America, like it’s ingrained in the soil. There’s something like that in Trinidad, there’s a lingering… I don’t know what word to use other than darkness, but we put a humour to it. Like we have to laugh it off all the time… Trinidad, in a way, is built from something very negative but we are trying to make it positive.”

Alice O’Keeffe is the Books Editor at The Bookseller.

Curated from The Bookseller.

- Life’s Work: An Interview with Danielle Steel

- Richard Flanagan interview: Winning the Booker was ‘a catastrophe of good fortune’

- “The literature of today will not be completely cut off from the literature of the future”: Interview with Mozid Mahmud

- Abdulrazak Gurnah Refuses to Be Boxed In: ‘I Represent Me’

- When asked what I follow/believe, my answer is easy. ‘Les Cook’