Mozid Mahmud’s Memorial Club immerses us in the worlds of Hasan and Bilu as they navigate class struggles, gender discrimination, and sexual assaults, creating a vivid and complex portrait of today’s Bangladeshi society

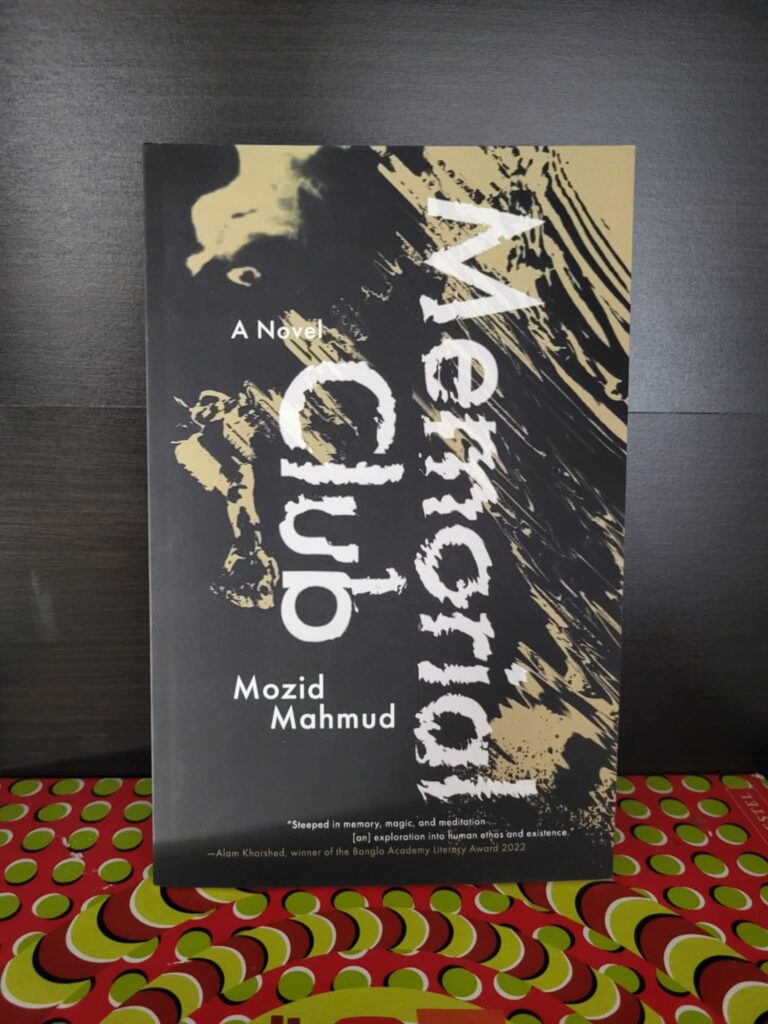

“Months later when Hasan finds himself at the rehabilitation center in Shyamoli, he will remember this dream.” Thus starts Mozid Mahmud’s first novel, Memorial Club. The novel was recently published in the States by Gaudy Boy, an imprint of Singapore Unbound.

In this novel, Hasan is a young journalist in Dhaka. He is disillusioned about his job, dissatisfied with his pregnant wife, and yearning for his independent-minded colleague, Bilu. One fateful night, he stumbles into a hapless, embarrassing situation that turns his life upside down. At the mercy of an unforgiving society for a crime he did not commit, he is haunted anew by memories of other victims of injustice he has known.

The novel has been hailed as an epic by Rahad Abir, author of Bengal Hound.

The novel carries us from the crowded streets of the capital city of Dhaka to the luminous mustard fields of Hasan’s childhood village.

“Nevertheless, the reasons why Hasan is in jail are not honorable. The accusations made against him are suspicious movement, robbery, hooliganism, and misconduct. Perhaps if he had engaged a lawyer, they could not have pinned all this on him. However, Hasan did not want one. He thought, Let’s see what happens.” (Memorial Club, Chapter: Nazareth Road)

CounterText: Where did you spend your childhood? Any words or memories that come to your mind?

MM: I spent my childhood in a village, a char built from the Padma silt. We were many brothers and sisters. Our family was large, the plot was full of various fruit trees. The palm trees of our house could be seen from a long distance.

I was the ninth of ten siblings. My brothers were much older than me. My eldest brother graduated before I was born. He wrote poetry and novels. Whatever he wrote he would keep it in a trunk. Later in life, he turned into a religious person and didn’t consider writing poetry to be a good thing.

Günter Gaus, “Conversation with Hannah Arendt,” from the Series Zur Person (1964)

My other brother, Abdul Khalek Biswas, gained fame as a poet in our district at a young age. It was the time of the Independence War of 1971. His poem, ‘Sonar Bangla Swadhin Holo,’ was sung by poets and sold in village markets. He joined the war, and went to India for training, where he was later joined by my older brother. Soon our house became a camp for freedom fighters. The Pakistani forces burned our house. We were stranded, our whole village, for some time.

Political tensions, unrest, and food shortages of the post-war era had an impact on me. Several political assassinations and seizures of power happened when I was a schoolboy. Political unrest and trauma still work in me. That is why I cannot come to any conclusion about what is happening in our national life and even in my personal life.

The Capital of Literary Bengal, by Mozid Mahmud

CounterText: How did you come to writing?

MM: I don’t remember exactly when and how I started writing. Before I went to school, I knew I was a poet, I would be a famous poet one day. I did not know what one needed to be a poet. I used to sit alone in paddy fields, watching the sunrise and sunset by the river, always muttering something. Because my brothers were poets, poets would come to read their poetry at our house. Punthi (folk epics) were recited almost every day at our house; people of all ages and genders in the area came to listen to those poems. People came to attend readings of Bishad-Shindu. During all this, I became a writer.

However, there was a book that contributed the most to my mental growth. I read it several times before my 5th grade. I am talking about Maxim Gorky’s My Childhood. Upon reading it, I would begin to feel like a character of Gorky’s, wandering around and dreaming of going to Kazan University.

CounterText: What challenges, if any, do you face in Bangladesh as an author these days? How are you dealing with them?

MM: Life in Bangladesh has become more complex lately for a writer. You don’t see respectable figures like Rabindranath, Jasimuddin, and Jibanananda anymore. They have almost disappeared. Up to the beginning of the 20th century, writers were much more local, confined to their countries and regions. But today they are largely international. Readers have also changed. It can be said that the lifespan of any good poem today is a few hours, thanks to the introduction of social media. However, nothing has been essential to me except my writing. I have understood only one thing: hostility from the media or any quarter cannot stop a writer completely; if a writer has something to say, they might as well say it to themselves.

CounterText: How many books have you published so far?

MM: I have published 60 books so far. Mahfujamangal is my first book of poetry. It was published in 1989. But before that I published two other books: Boutubani Phule Deshe and Makarsa O Rajnigandha. Boutubani Phule Deshe is a book of children’s poems. Makarsa O Rajnigandha is a collection of stories. I was a teenager when the books were published. Having a book published has always been exciting for me. When my first book was published, I couldn’t sleep at night!

CounterText: Is there any of your books that you want to mention here?

MM: My poetry collection, Mahfuzamangal, is widely known and widely read in Bangladesh. It has already gone through more than twenty editions. It was first printed by Pabna Bulbul Art Press. Before the publication of this collection, many poets warned me that I would have to leave the country for this. I wrote the book in just a few months – I was so emotional. I read it to my friends. After thirty-six years of its publication, readers still show enormous interest in this book.

CounterText: Tell us about Memorial Club.

MM: Memorial Club is a narrative fiction. It reflects my thoughts on social life, religion, and politics. Through Hasan, my protagonist, I wanted to capture the cruelty of people to each other. Our society is unforgiving; it constantly refuses to remember the victims of injustice.

“There was a madman in our village … He tried to give the police reason to arrest him, but his efforts failed… In the end, he made himself a cage, placed it on the balcony of his house, and sat locked in it…” (Memorial Club, Chapter: Nazareth Road)

CounterText: What will the literature of tomorrow be like?

MM: The literature of today and the future will not be completely cut off from each other. Human pains and sufferings, love and affection, birth and mortality will remain the same. Today we do not understand the language of the Charyapada, but we still read it. It is a part of our history. Similarly, the writings of Michael, Rabindranath, and Nazrul have become a part of our history. But history will not stop there. Our writings today will be a part of our history tomorrow. Nothing will be lost.

In Conversation with Mozid Mahmud. December 16, 2024.

- Life’s Work: An Interview with Danielle Steel

- Richard Flanagan interview: Winning the Booker was ‘a catastrophe of good fortune’

- “The literature of today will not be completely cut off from the literature of the future”: Interview with Mozid Mahmud

- Abdulrazak Gurnah Refuses to Be Boxed In: ‘I Represent Me’

- When asked what I follow/believe, my answer is easy. ‘Les Cook’