This interview, by HOPE REESE, was curated from The Hazlitt.

In the fall of 2006, Doree Shafrir started writing for the now-defunct Gawker, a media site that came to life at the dawn of online journalism—shifting standards for how stories were produced and ushering in a new age of media consumption. Shafrir, now a senior culture writer at BuzzFeed, lived in New York for almost a decade, where she “worked for startups, wrote about startups, had a lot of friends who worked for startups.”

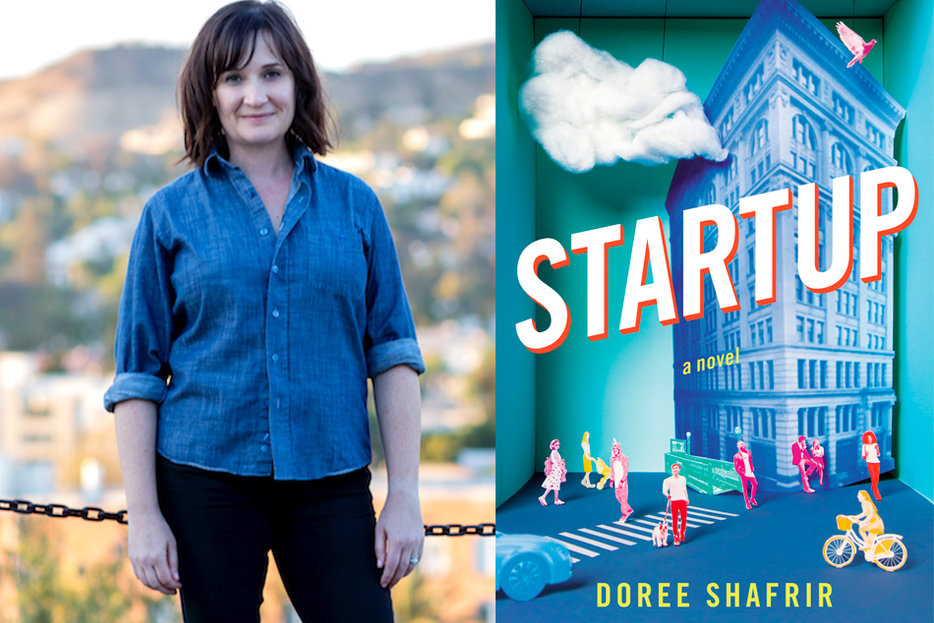

In her debut novel, Startup (Little, Brown and Company), Shafrir draws on her experiences from both the online journalism industry and the startup scene in New York to illustrate the current state of tech startups and the strange symbiosis between app-developers, venture capitalists, and tech reporters. The novel, a satire, is eerily on-point in its illustration of this universe—especially when it comes to gender dynamics.

Hope Reese: Your novel illustrates the frantic pace of online journalism today. Can you talk about your own experience of this? And is there something specific to tech journalism that separates it from the media industry as a whole?

Doree Shafrir: The first time I really experienced this was when I started working for Gawker. We had quotas for how many posts we had to do a day—I think I had to do six posts a day. Some of my colleagues had to do like ten or twelve posts a day. It was a lot more aggregation at the time, but still, that’s a lot. It was just this sort of constant frantic-ness. Once you’d finished something, it was, “What are you going to post next? When is it going to go up? Are we late on this?” There was a lot of pressure to have stuff up quickly.

Is it worse in tech journalism, specifically? I mean, I don’t think it’s better. It’s something that is endemic to online journalism, certainly. One thing about tech journalism is that it is a pretty insular world, in the same way that a lot of other areas of journalism, like music journalism or political reporting, are. You know all the people in your world, and I think there’s just a lot competition within each circle.

If you had to give advice to someone entering a career in journalism, like the character in your novel, Katya, do you say, “Okay, go compete, and you have to be fast”? How do you navigate that world if you’re twenty-four years old today?

One thing that we’re seeing now is the industry is changing really fast. When I started at Gawker, the shift from print to online was still not complete. Obviously, Gawker was always just digital, but there was still this question: How long will Internet journalism be around? How much do we have to invest in it? So it wasn’t taken very seriously by a lot of companies. A lot of websites were considered second-tier, and for people graduating, there was still this idea that going into print journalism was more prestigious.

Of course, that all changed pretty quickly, and you’re seeing a similar thing now with video. There was a lot of skepticism about video. People thought it wasn’t serious, or that online video wasn’t ever going to be invested in as much as TV was. All things that remind me a lot of what people were saying about online journalism ten years ago.

Companies are laying off people who are only writers, saying that they’re going to concentrate on video. That’s something that’s been set in motion. It’s just really important for young journalists to learn as many skills as they can, whether it’s audio or video. The days when you can get away with just writing are going to be over pretty soon.

And as someone who is just a writer, I see a world where I could be writing my own demise, but that’s just reality right now.

What made you set the story in New York? What’s unique to that city’s startup scene versus Silicon Valley?

So, for one, I lived in New York for about nine years and worked for startups, wrote about startups, had a lot of friends who worked for startups. When I wasn’t working for startups, I definitely considered myself startup-adjacent, and so pretty well versed in that world.

I also thought it was a fascinating world that no one had really captured in fiction. So much of the pop culture around tech is centered on Silicon Valley, which makes sense because it is the epicenter––but Silicon Valley is also a place where tech is the only game in town. New York has this burgeoning tech scene, but there are so many other well-established industries in New York. Startups don’t quite yet have the same social capital that, say, Wall Street or fashion or even media do. So I wanted to explore that tension a little bit.

Do you watch the HBO show Silicon Valley? I’ve heard people in the tech industry say they can’t watch it because of how on-point it is. Your novel is similar—it really captures the startup scene so well.

I really enjoy Silicon Valley—I think it’s so smart and funny. But it started as a very incisive satire, and now it’s kind of hard to tell who they’re satirizing. So much of the tech world in San Francisco and Silicon Valley loves the show—they even have cameos on it. It’s like, what is the relationship between the “real world,” and the show? And who is the show targeting?

So, who is your book targeting, would you say?

My book is targeting the startup world as a whole. And, particularly, men in the startup world. It’s also targeting hypocrisy overall, whether it’s coming from a man or a woman.

People in Silicon Valley like to say that they “move fast and break things,” and I want to show how that maybe isn’t the best way to conduct yourself. And there’s this idea that what they’re doing is just for the good of humanity, which can mask some not-so-great behavior. And that this supposedly “brave new world” has nonetheless taken on some of the worst aspects of the old way of doing things.

You describe this “team spirit” workplace culture that demands coworkers engage in things like sunrise workout raves and pole dancing classes. How does this compare to what work was like when you were in your twenties?

It seems like my younger coworkers are all friends, and they’re always meeting up. There are always emails going around of like, “I need a new roomie.” I know that some of them live together, some of them date each other. It just does really seem like their personal and professional lives are just completely one.

That’s not the way that I need to spend my time. But now there are more people at BuzzFeed who are in their thirties, even in their forties—and there’s not the expectation that I need to participate in that kind of stuff. But if I were on another team where people were a lot younger, and the participation in these, let’s call them “extracurriculars,” was expected, I might feel alienated.

Do you think this is a generational thing, or does technology have an impact on it?

Tech enables it, no question. Instagram feels very aspirational to me. Tumblr is the place where you might go to be sad, but Instagram is the place where you go to show off all the great things in your life. I think that it’s definitely exaggerated by social media.

I think people do age out. A big reason the character of Sabrina in the novel feels so alienated is because she has two kids and a husband who’s not particularly helpful, so she has to be home at six o’clock every night to relieve the nanny. So not only does she have to leave work earlier than all of her colleagues, but she can’t go out with her colleagues after work. So there’s a difference in lifestyle that has made it so that she really can’t participate on this level with her younger co-workers, even if she really wanted to.

Even though in New York, like you were saying, there is this extended adolescence, eventually a lot of people do get married and do have kids, and their lifestyles do change. So I think getting older does mean that you’re probably not participating in these events as much as you used to.

In Startup, everyone is constantly using apps, like a Tinder for apartment rentals, many I’d never heard of. Did you make them up? If so, some of the ideas are brilliant!

Any that are not immediately familiar to you are ones I made up. That being said, several times, what has happened since I finished the book is I’ve seen stuff about apps that sound very similar to apps I made up. So it just kind of says to me that A, there are no original ideas and B, I wasn’t that far off in my making up of these apps.

You explore socio-economic status in the startup world. Can you talk about that?

New York is really expensive to live, and yet a lot of young people want to live there. So it can be confusing as a young person to look around and to see your friends, who you know probably don’t make more than $40,000, maybe $50,000 a year, and think, “Huh, that’s weird—they have a one bedroom apartment in Williamsburg. How do they afford that?”

There are these moments when you realize that your friend is an heiress, or has well-off parents who are paying their rent. It gives people this leg up, and they feel they’re just entitled to it, but it makes it so much harder for everyone else. If you’re paying student loans and you’re not getting help from your parents and you are making $40,000 a year, how are you living? How does that affect your quality of life? How does that affect your mental health? How does that affect the kind of jobs you can get? How do you feel when your friend whose parents who are paying their rent invite you out to dinner and they choose a really expensive restaurant because they can just put their share on a credit card, and you don’t have a credit card?

Also: you always are jealous of the people who have more than you. From the outside, Sabrina is doing fine. She and her husband own an apartment in Park Slope. She has a job, her husband has a good job. They have all the trappings of a typical upper-middle class life in New York City. But all she can think about is her very successful friend from college who has a brownstone, and gets obsessed with her friend from grad school who wrote a best-selling series of books and is also super rich. There are always going to be people who have more than you, so one thing that I finally learned when I was in New York is that it actually will bring you down and impede your own success if you are just constantly letting that stuff get to you. It can really get to you. But if you’re just always focused on other people you’re not going to work on yourself.

Same with the Katya character. Katya definitely sees herself as this scrappy outsider who went to public school, got a scholarship to NYU, lived at home. And certainly she is from a middle-class, even working class background—but she also has privilege that she doesn’t always want to acknowledge.

People are often blind to their own privilege, no matter where they land on the spectrum.

In the novel, you illustrate two workplace relationships that turn romantic or sexual. What makes this kind of thing different in the digital age?

I wanted to show how intertwined the personal and professional lives of people, especially people in their twenties, are now, and how a lot of those boundaries get blurred. And I wanted to show how there is a lot of this confusion, I think, especially in these companies that don’t have HR departments. HR is often the last department hired, so you can have a 50- or 100- even 200-person company with no HR department—and stuff’s gonna happen when there’s no one there to say, “Hey, this is not supposed to be happening.” I think that leads to a lot of confusion.

I’ve certainly witnessed enough situations where an older editor is behaving inappropriately with a younger writer, and there’s a power imbalance that, sometimes, the younger writer isn’t fully aware of, or thinks she’s in control of—and she’s really not. I wanted to explore that.

There’s a scene in the novel, in a meeting full of men, where one guy says they’re living in a “male-hostile moment.” It’s a hilarious term—did you make it up?

I did. Certainly, if men are having those conversations among themselves, I have not been privy to them—that’s kind of what I wanted to get at, that this is just a conversation amongst men, and they feel very free to say things that you and I would be horrified by, and challenge. But everyone in that room is like, “Oh yeah, totally, totally, nail her.”

You see sentiments like that expressed on Twitter or Reddit—you know, men re-conceiving themselves as victims. I wanted that to be an aspect of the story, too. How the men in this story know that Mack’s behavior reflects badly on the company, but they’re not really saying that what he did was so terrible. They’re just like, “The optics of it are bad, this is a bad moment for a white guy to be accused of sexual harassment, so you gotta kind of chill.” But the actual actions are not really condemned.

In light of recent allegations about discrimination against women at companies such as Uber and Google, the story feels especially timely.

When I started it, the two big sexual harassment in tech things that were going on were the Whitney Wolfe Tinder lawsuit and the Ellen Pao Kleiner Perkins trial regarding a gender discrimination suit she filed against her then employer, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. I was kind of like, well, these situations are a bit at the forefront of my mind, but there was a part of me that was like, “Hmm, this book might feel dated by the time it comes out.”

So on the one hand, it’s great to feel like the book is very of the moment and exploring new themes and issues that people are really talking about right now. On the other hand, it is really fucking depressing that this book is so of the moment. Why is this stuff still going on? This is crazy to me.

I obviously had no idea that these sexual harassment allegations at Uber or any of these other places would come out and that people would really be talking about gender discrimination and sexual harassment in check and that it would still be such a hot-button topic. But when are we going to figure this out? Come on.

Interview curated from The Hazlitt.