Interview by Spencer Quong May 21, 2019. Curated from The Paris Review.

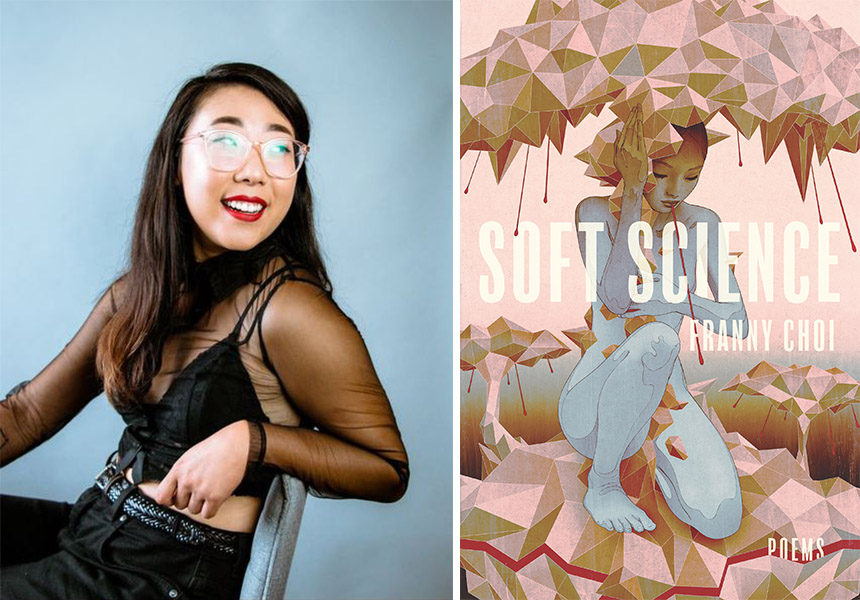

Franny Choi isn’t done thinking about cyborgs. When we met two weeks before the release of her latest collection Soft Science, she told me she was still discovering AI ideas she wished she could have addressed in her poems. Reckoning with the mythology of a “finished product,” Choi is coming to terms with having a book that is both out in the world and still in progress. The process isn’t easy: as one of Choi’s cyborgs says, questioning reality makes her feel “a / little insecure / a little embarrassed haha.” But to be insecure, or still in progress, should never be mistaken for being incomplete.

Soft Science asks what it means to live as a queer Asian American femme, someone “made a technology for other people’s desire.” How do we distinguish between the constructed pieces that have been imposed on us versus the parts of our identity that we’ve chosen? Are they always distinct? The voice of Soft Science is often corrupting: Choi inhabits colonized language and uses it to her own ends. In the poem “The Cyborg Wants To Make Sure She heard You Right,” Choi runs negative comments directed at her on Twitter back and forth through Google Translate until the language is transformed into something new. By repurposing language, Choi offers up a record of what is happening to our bodies and minds under whiteness and capitalism, and the beginnings of a way forward.

Choi is the co-host of the podcast VS, a member of the Dark Noise Collective, and will begin teaching this fall at Williams College. Soft Science is Choi’s second full-length collection, following Floating, Brilliant, Gone and her chapbook, Death by Sex Machine. Her poem, “Amid Rising Tensions on the Korean Peninsula” also features in our spring issue.

INTERVIEWER: How did Soft Science begin?

CHOI: The book came out of writing a series of poems that were inspired by and in the voice of a character from the film Ex Machina, Kyoko. When I watched that film, I had a particular combination of emotional responses that provoked a desire to write. A mix of love, confusion, and outrage. I started writing to try to understand what I was feeling about her, and then quickly realized that the poems were speaking to other poems about my own experience as an Asian American woman—as a queer Asian American woman—about moving through the world in a body that had been made an object of desire, fantasy, and power. Living as a soft, fleshy objectified human of the world.

INTERVIEWER: Right. Living as a soft, fleshy person but also a person that contains metal?

CHOI: Yes, as a person who’s been made a technology for other people’s desires in a particularly visible way. We all have intimate relationships with machines—that’s part of the definition of being a human, the ability to use tools, right? But I think it’s foregrounded for different groups of people in different ways.

INTERVIEWER: There’s a poem in your chapbook that begins: “Have you ever wanted a new body?” On the one hand, that’s a thought that could be really destructive for a queer person—a voice that says, Have you ever wanted a straight body? Or a cis body? But then there’s also a really beautiful way to read that question: Can we be shapeshifters? Both deeply felt and fluid?

In “Bad Daughter,” the protagonist of the poem “kept showing / up in new clothes, new names; then leaving.” Is there both excitement and dread to shapeshifting?

CHOI: The first time I was really able to envision femininity as a kind of power was while watching Paris is Burning in college, encountering the world of drag for the first time. The knowledge that my femmeness was something I could put on and take off, something I could play with and shapeshift into, made me feel so in control of it, and made me feel powerful for choosing it. The ability to alter our images and to play with the way that we present our bodies is a fundamental queer and femme superpower. The book dives into that and says, if we continue down that line of thought, then what other possibilities are opened up?

INTERVIEWER: How did writing the poems for Soft Science shift your understanding of your identities?

CHOI: Blurring the confines of my own identity is a way of embodying a kind of queerness. I started to think about my affinity for certain images, like the cyborg and the squid, the cephalopods. There are a lot of cephalopods in this book and I keep writing about them—because octopuses will inherit the earth. My affinity for certain images was a way of taking up the incoherence of my gender identity. It’s weird—we think that we understand ourselves and then use that understanding to write poems about our bodies, but it’s just as common in my experience to have written poems about my body for five years and then be like, Oh, that’s who I am?

INTERVIEWER: Is that daunting? The uncertainty, the endless discovery—it’s exciting, I’d think. But does it get tiring or difficult?

CHOI: I guess it’s a little scary, but it’s mostly exciting. I think of that poem you mentioned that begins “Have you ever wanted a new body?” There’s a lot of freedom in imagining that you can escape the confines of the body that you were handed. It’s an exercise in imagining, in feeling free.

Though sometimes I do wonder if it’s a cop-out to say, I’m not a woman, I’m a squid. Since it’s not exactly true, even if it does help me think about how I identify.

INTERVIEWER: Why do you think of it as a cop-out?

CHOI: I don’t know—I guess I’m in an active process of questioning my gender identity, and it feels like a way to disavow cis privilege sometimes, and to turn away from that privilege instead of reckoning with it. But I think maybe the questioning also has to be part of that process of reckoning.

INTERVIEWER: I remember in one episode of VS, your podcast with Danez Smith, you spoke about looking for a definition of Korean poetics. You were reckoning with a similar tension between your distance and intimacy to Korean-ness and the Korean peninsula. Could you talk about writing from such a position?

CHOI: It’s a weird thing to want to write for my people, to put my communities at the center of my artistic process, and also to know that on some level I’m writing for an American audience. To not really understand how Korean readers might take me or interpret my work. And there’s also the kind of sneaky, shitty feeling that you’re explaining what it means to be Korean to people who aren’t. It’s unsettling. I think of myself as a Korean American poet, I know that I am, but I don’t have a really solid understanding of contemporary Korean poetry except for a few folks in translation.

I think it’s easy in all of that to feel like a fraud. But people of a diaspora—who are on the margins between two different worlds—are often made to feel like frauds for anything we don’t understand about either world. Any distance that I might have from the poetry of Korea is also a distance that other people like me will relate to. I hope so, at least. That’s also part of our history. If there’s an identity of Koreans in the diaspora then distance to the homeland is part of it.

INTERVIEWER: I think that’s an idea that the cyborg embodies, too. It resists strict categorization. It might be both machine and human. You can be both Korean and have ways in which you are unfamiliar with Korea.

You’re also reminding me of lines from the first poem in the collection: “some of us are born in orbit / so learn / to commune with miles of darkness.” Some of us are born into missing, stolen or erased histories—be they queer or Korean histories. But your poetry seems to find a way to revel in the silences, or to continue to seek answers despite the “darkness.”

CHOI: Poetry helps me to have a conversation with history. It’s hard for me to understand the past as a series of events. Poetry allows me to understand history by embodying it from my own subjective position and to track the ways that those imprints of the past show up in my sentences.

What you said about the silences in history is really interesting and exciting. If we engage with history as a conversation, then those silences are actually necessary in order to have that conversation, right? If somebody is just speaking for an hour, that’s not a conversation, that’s a podcast.

There has to be space. Space is an unknowing for us to engage with. There has to be room for questions. Silence is not just a space to mark a death, it’s also an opportunity to reveal. So I hope that building silence into the poem, whether that’s a literal caesura on the page or a word that’s redacted or if it’s just the things that are unsaid in other ways, allows the poem some room to breathe and allows the reader a space to interact with it. A little alcove in the poem so you can sit inside it and not just look at it from afar.

INTERVIEWER: Right. Your poems really do call the reader to participate. I’m thinking also of the reoccurrence of words like mouth and bones and skin. At times, the language terrifies me because it’s draws attention to these really vulnerable parts of our bodies. But the attention is also wonderful. I’m reading and thinking, I’m so aware that I have hands and mouth and skin!

CHOI: That is a great thing. I’ve succeeded if people read my book and think, Oh my god, I have hands and skin.

INTERVIEWER: What compels you about the language of the body?

CHOI: I mean having a body is such a fucking trip, you know? The other day I was talking to Danez Smith, and they were like, Ugh I hate having a body, I wish I could just be a presence—which I totally sometimes relate to. But also, the body—our materiality—is the only way that we know how to exist in the world.

I’m always drawn to the language of the body because that language, which I was born into, has completely determined how I’ve been allowed to imagine myself. The first time I ever made a chapbook of my poems—printed at a FedEx and stapled together—I called it Women Only Write Body Poems, which is a joke that I still find funny. But for better or for worse, it’s a job that women who write have always found themselves doing.

But despite some of the poems in the book, I don’t actually think that the total transcendence of our material forms is what I’m after, because that also seems like a way of checking out of the whole problem. I think that I want to learn how to live in a dynamic and fruitful and sexy relationship with the body.

INTERVIEWER: When you talked about it as a job—who is that labor for?

CHOI: I think it’s a labor to remind myself that I have a body, but to everybody else, my body walks into the room before I do. Or before whatever I consider the rest of me. People see me as a 5’3” Asian woman before they know anything about what I call myself in my poems—usually. Given that this image of myself precedes me, what do I do with that body that’s walked into the room, that’s walked into the room of people’s minds? I think that question is an interesting one. It could be a trap, but it could also be a chance to play.

INTERVIEWER: What does it feel like to read your poems out loud?

CHOI: I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me that before. I love reading my work aloud. That’s part of my writing process, anyway. I’m always thinking about what they sound like as they’re read in front of a group of people. I love what happens to a poem when it enters a room of people. I love learning about a poem in the air.

Slam has taught me what kinds of poems are immediately accessible and exciting to people—and I love reading those poems. But I also really love reading work that I think no one outside of my own brain will understand, or get anything out of. I love seeing what happens, and those times that it does do something besides confuse and alienate people are exciting. I like being surprised by my own work. In the process of writing, of course, but also in the process of reading it out loud.

INTERVIEWER: Elsewhere, you’ve spoken about using form as a means to reveal, rather than obscure. Can you say more about that idea?

CHOI: I think it’s sort of magic, right? To take an image that we think we’re already familiar with, and to rearrange it on a language level in order to show something new about it.

I think when we play with form what we’re engaging with is the technology of the poem. And so when I play with form, what I’m doing is saying that I’m a coauthor of this text along with the machine of poetry—the mechanics of the lyric—in order to produce this thing. The mechanics of the poem and I are collaborating in order to make something new with language that didn’t belong to either of us to begin with. I’m still in the process of figuring out what a cyborg poetics is, but that feels like a clue to me.

INTERVIEWER: Were you surprised by anything in the process of writing this collection?

CHOI: I think I’m still in the process of learning about the book. I’m not done thinking about cyborg identity. I’m not done thinking about machines. I’m not done thinking about machines that think. I don’t know what to do with the fact that I’m not done thinking about them, but I think I that it’s okay not to be done thinking about something when the ostensible final product is in the world.

When I finished the draft and sent it in, the next week people kept sending me articles, saying, Have you heard about this robot? Have you heard about this new weird thing about AI? And I just kept thinking, Oh no, I didn’t get it all. But I think there’s something beautiful about a book that’s learning how to think about itself. I hope that it’s okay for it to still be trying to figure itself out.

INTERVIEWER: For an individual poem, how do you know when to set it aside?

CHOI I think a poem is finished when I know what every line is doing in it. Even if I don’t know what every line means, I know that every word has a job. And sometimes that job is just to sing or to reverberate. Or to be confusing.

I also know that a poem is done when anything I try to do to it makes it worse. Sometimes it feels like a poem’s not done and so I keep trying to hack at it but everything I do deadens it. I have to think, this poem might feel incomplete but that’s where it needs to live.

Spencer Quong is a writer from the Yukon Territory, Canada. He currently lives and works in New York.

Interview curated from The Paris Review.